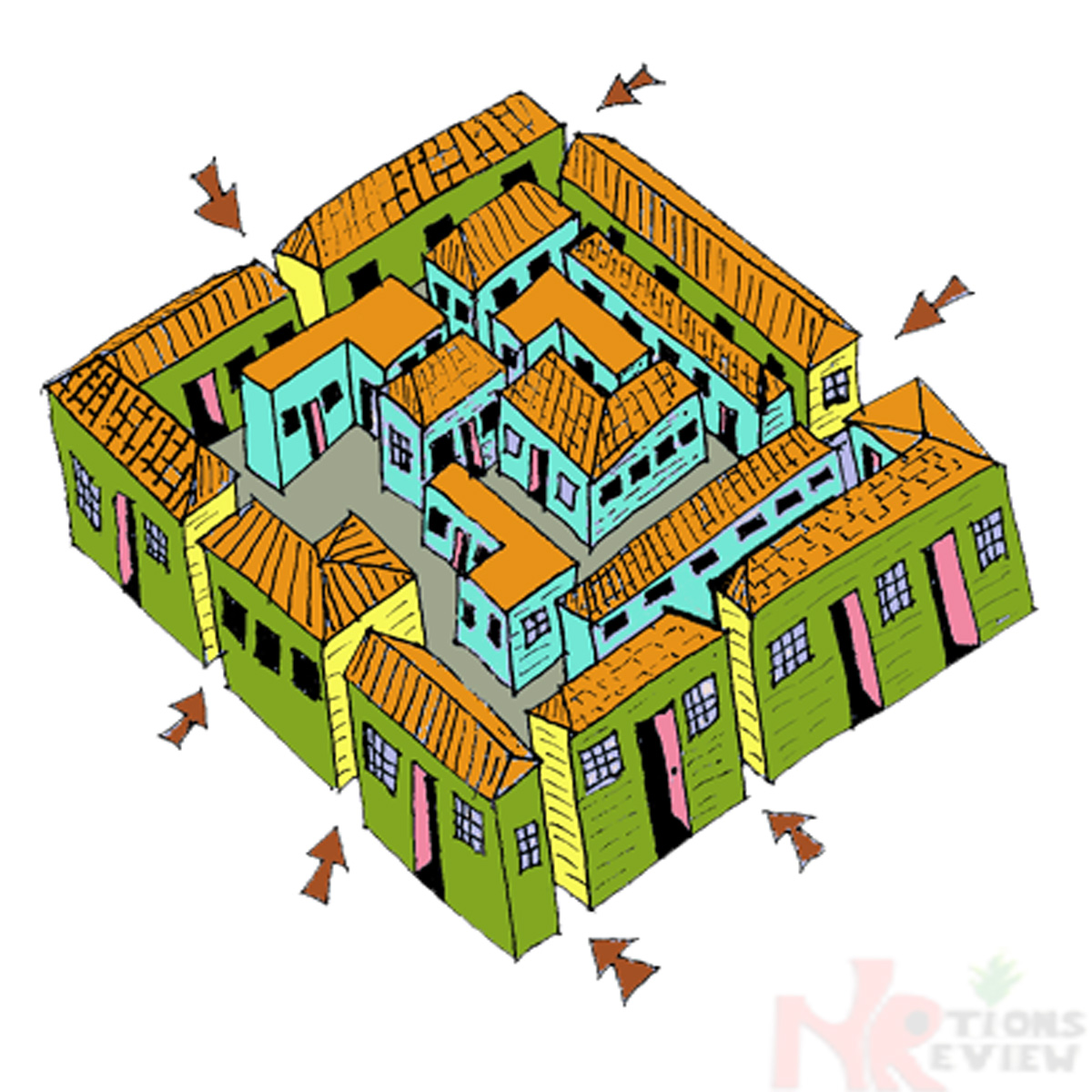

A traditional African village serves as the country home of township dwellers. It is only during festivity times that all sons and daughters come together like a gathering of a social club. Native homes provide the same air of recreation one feels when visiting strange lands. But it is much easier to get lost in a small African village than in a big urban township. The situation is like an ant getting lost in a teacup yet easily navigating its way out of a bigger pot. Ancient community settlements have a typical maze-housing layout. The maze walls are actually lined up houses separated by narrow passages between them. The fact that this “design” is ubiquitous arouses curiosity. It is like all ancient community settlements assume an unwritten ‘land use law’ that guarantees that the end result of a town’s housing layout must be a complete maze. This is the paradox of sprouting haphazard buildings that plan native towns.

It is standard practice to plan towns. Planning proposes a visionary layout that zones, classes and accommodates the present population as well as caters to the needs of future generations. In planned modern townships, road width could be small but traditional settlements grow by the gradual addition of buildings to the initial ones until they collectively give a picture of outward growth from the centre like encrusting rust. This does not suggest a lack of vision of the inhabitants but a practice induced by an underlying culture.

In Greek mythology, the story of the Minotaur narrates Prince Theseus’ adventure culminating in the killing of the human-devouring hideous monster; the human-like creature with the head of a bull, housed in the middle of an “inscrutable and most wondrous” labyrinth. The “search, find and destroy the monster or be eaten by it” adventure, was potent with the danger of ‘who finds whom’ first, hence the ingenuity of the design of the maze becomes important. The labyrinth of King Minors, (the arena for which the annual draw lot for the sons and daughters of Athens to be fed to the ravenous appetite of this brute in Crete) was built by the genius of Daedalus. In compliments, the path is described as zigzagged and wriggled.

This illustrates that the fascination with mazes had been exploited in the distant past. But the paradox is that complicated high-quality mazes are effortlessly and naturally constructed in Africa without an initial plan. A maze is a common feature in children’s fun pads. It is great fun to find your way into the centre of the labyrinth to find a treasure or to retrace your way out of it at escaping from a villain. Cultural peoples in traditional villages unconsciously recreate this life-size fun when they erect their huts haphazardly due to the absence of a town-plan blueprint.

Ancestral land is scarce hence every space is golden. If all communal lands were planned to cater for roads, playgrounds and more, there would be less land for housing purposes. Besides, because of the traditionally sustained extended family culture, everyone likes to live close to the other as a commune of people that are closely related by the language they speak. This is the philosophy underlying the maze housing project development.

The ability to scramble your way in and out of the maze gives the same sense of achievement as finding a treasure at the centre of a maze. African mazes are complex designs yet they are not designed at all.

In Okrika, a community in Nigeria, the only sign of planning in the town is the St. Peter’s Church built in 1923. It is surprisingly bigger than most of the newer churches built 40 years after. It occupies a very impressive large area. Could the ancient people have thought of a great leap in the growth of Christianity? No, but there was a reason. The Church had to be big to occupy all the land so-called “evil forest” as a way to stop fetish practices associated with its use and change the people to the part of Godly worship. The land was used to bury outcasts of ancient society. And since no one dared to live there, the early missionaries found it an easy piece of land to wrestle out of the conservative inhabitants.

In deltaic areas, habitable dry land is usually small. Families reclaim land from the river using tree stumps or dried-out fibrous mud over which houses are planted. The available land is shared as the need arises and the property developer’s consideration for a passage to his house is only secondary. Houses are built so close to each other that domestic animals have gained confidence despite the dangers of human proximity in sharing a rite of passage along those narrow alleys. It is like Robin Hood and Little John on the narrow bridge. Sometimes, one has to embrace the wall for the oncoming other to pass.

Each little passage an individual contributes to the community from his unused land links up with other peoples’ passages to form the narrow road between buildings around the town. Sometimes a winding path could lead one unknowingly back to his starting position and just like a game, it could continue until eternity if no one comes to your rescue. That is the magic of the African maze.

This maze setting has its advantage; it is easier for an indigene to decipher his route through the maze than for a stranger. To find your way around is by noting landmarks or peculiar architecture but sometimes, all the houses are of the same design; mud houses of the same colour with thatched roofs or houses with no windows.

If at a turn in the winding road path, one finds himself face to face with the dead centre of an H-shaped building, then that gives you away as a stranger; “Johnny has just come”. This knowledge of the correct path through a maze is the asset of those who grew up in the village. During inter-tribal wars, the maze affords the opportunity to ambush a dispersed invading enemy. No foreign thief can escape easily. Growing up in the village implants a “village mentality” as different from the mentality of the exposure to township dwelling. Yet this love to stay at home is the key to the survival of traditional beliefs, territorial defence, and architecture.

Within the maze are many ingenious ideas. Everyone can own the space above another man’s house. People who can afford it can own land on the ground and the sky above is still free for grabs. This makes some houses to look bewitching and the inhabitants to appear like witches living in a mushroom-like structure; slender at the base and broad at the top. Sometimes, a one-room plot is built up to five stories with the stairway winding around the structure like a boa constrictor. For the lack of land, some of these multiple one-room structures are as high as a palm tree with the stairway barely wide enough for one person’s passage at a time. This could explain the inference of the African as “living on trees”.

Another common feature is; such buildings that extend over footpaths and the house owners consciously allowing passage through the house like a tunnel or duct. You live upstairs while the entire community traverses under your house, literally, passing through the portion that is bridging their footpath.

The beauty of a town is in its peculiarity, even if the structures are in disarray; it is unique to serve tourism needs. Its architecture could lack all the complexity or expectations of rational design, yet its oddity would remain a landmark. The African village is of a simple layout but a complex result that could challenge even the genius of Daedalus.